Irish Independent, February 23, 2013

In one of his hundreds of sports columns from the 1970s, Con Houlihan paid tribute to the great Welsh scrumhalf, Gareth Edwards, who at that time was at the pinnacle both of his game and of his fame. A fitting subject, then, for a writer who had a lifelong and particular passion for rugby.

Here’s the thing, though – although Edwards was the article’s subject, he wasn’t mentioned until two-thirds of the way through the piece. Before that, the author ruminated on the nestbuilding deficiencies of rooks, the resourcefulness of hens, the short stories of Ernest Hemingway, the poetry of Thomas Gray and the paintings of John Constable. Finally, after fifteen paragraphs on such matters, he got round to praising Edwards for his character, his resilience and the poetry that he brought to his beloved game.

Here’s the thing, though – although Edwards was the article’s subject, he wasn’t mentioned until two-thirds of the way through the piece. Before that, the author ruminated on the nestbuilding deficiencies of rooks, the resourcefulness of hens, the short stories of Ernest Hemingway, the poetry of Thomas Gray and the paintings of John Constable. Finally, after fifteen paragraphs on such matters, he got round to praising Edwards for his character, his resilience and the poetry that he brought to his beloved game.

Here’s the other thing, though – the article was somehow all of a piece, the reader being persuaded by its conversational chattiness, its casual allusions, its quiet air of authority and its underlying conviction that sport, art, literature and the act of living were all intertwined as forms of human endeavour.

That was the Houlihan philosophy, and discursiveness was the Houlihan style, a style that lesser journalists copied at their peril. Indeed, some of them came a cropper in their attempt to imitate the inimitable. There was only ever one Con Houlihan.

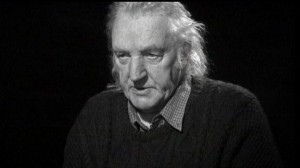

He first came to public attention in the early 1970s, a middle-aged man who arrived in Dublin out of nowhere (Castle Island, actually), began writing a backpage sports column for the Evening Press and almost immediately found thousands of readers who hung on his every word.

Those of us who were fortunate to know him remember well our early encounters with him. Dr Johnson was one of his great heroes and he was Johnsonian himself in all sorts of ways – his enormous frame and unkempt appearance, his brilliantly aphoristic pub chat (though where was his Boswell?), the clarity of his convictions, the acuity of his insights and the ease of his prose.

He was a wonderful teacher, too, though in an entirely unpedantic fashion. I recall showing him a theatre review I’d just written for the following morning’s Irish Press and he pointed to the first paragraph, a torturously prolix and pretensious sentence laden down with subordinate clauses. “That’s fine, boy”, he gently commented, “but you could also put it like this” – and he came up with a sentence of perhaps eleven words that pithily said everything I’d been labouring to say in four times that length.

Indeed, he hated obscurantism and obfuscation, whether in thought or in writing (George Orwell was another hero), while his view of art and literature was similarly direct, adhering to Johnson’s dictum that “nothing can please many, and please long, but just representations of general nature”.

And, like Johnson, he wrote for the common reader, whom he treated with the respect due to those who might never have come across the poetry of Edward Thomas or the paintings of Cezanne until Con mentioned them but who could be trusted keep their minds open to the possibilities of new and enriching experiences.

That was one of his great gifts – to make the seemingly unapproachable entirely accessible to as wide an audience as possible. And that’s because he saw no distinction between high and low art if both were honestly and movingly expressed. Indeed, he refused utterly to compartmentalise experience – whether it took place in an art gallery or on a football terrace – into categories of any kind.

And thus, when one night I played him a newly-released Randy Newman album, the singersongwriter’s vignettes of an inward-looking American Deep South found their way into Con’s column the next day when he observed that the underperforming Kerry team of the time had “as much chance of redemption as Randy Newman’s good old boys”.

A student of Daniel Corkery in University College Cork, Con was never persuaded by Corkery’s narrow view of a pure, insular Ireland – indeed, his first journalistic writings, commissioned by the Kerryman, were so courageously radical as to be dangerous to himself, including a withering attack on Charles Haughey long before anyone else dared to say anything bad about the man, and forthright condemnations of the atrocities being committed in the name of Irish nationalism.

When he came to Dublin and the Evening Press editor, Sean Ward, asked him to write the backpage column that had been unfilled since the death of Joe Sherwood, Con took to it like one of his beloved ducks took to the Grand Canal, near which he lived for all of his later life. Soon, fans around the country were impatiently waiting for copies of the evening paper to arrive at their local shop – Waiting for Houlihan, as Maurice Healy’s 2004 television profile was aptly called.

After a while, the weekly column became thrice-weekly and he also began a fortnightly Tributaries column, which gave him the space to write at length about art, literature or whatever other cultural matters took his fancy. And while the other Dublin papers constantly tried to lure him away, offering all sorts of freedoms and financial blandishments, his loyalty to the Evening Press and to its editor remained constant.

Indeed, no matter how early you entered the newsroom, he was there before you, seated at the long sports desk and handwriting his paragraphs with such assurance about what he wanted to say that there was seldom, if ever, need for him to delete a word or phrase and replace it with another.

Then, by 9am, he was gone to embrace the day and all its myriad possibilities – and the night, too, where he could be found absorbed in animated conversation in the Silver Swan or the Scotch House on Burgh Quay or in Mulligan’s of Poolbeg Street or in a variety of other hostelries unknown to all but the true connoisseur of chat and craic.

Yet though his devotion to the Evening Press was such that when the Irish Press group collapsed in 1995 he was left feeling bereft, he did undertake the occasional outside commission, especially the invitation by Allied Irish Bank to write a series of pieces on the towns of Ireland.

This was an ambitious undertaking but one that he accomplished with his customary flair, fluency, attention to historical detail and folklore, and love of place – not least when writing about his native Castle Island (he always insisted on the two words), describing it as “probably my favourite spot in the whole world” and noting that “the Australian Aborigines would understand; they have their sacred places”.

But telling insights and lovely asides abound throughout these pieces, as when he observes the wiles and guiles involved in buying or selling a cow at the Newcastle West fair, “it wasn’t enough to be a good judge…you needed an insight into the human mind beyond the scope of a professional psychiatrist”.

Or, when discussing the “raw new housing estates” of the generally unloved Finglas, he writes tenderly of their inhabitants, while also allowing himself teasing digressions – noting, for instance, that rural people often make better emigrants than their urban counterparts to such outwardly impersonal centres as London and Boston: “they are not as lonely as city people might be because in many cases they have come away from loneliness”.

And while he recognises that “the good people” of Dalkey might deem it intrusive for an outsider to write about their historic and fashionable village, “nobody expressed the essence of Paris better than Emile Zola, a native of Provence, and Georges Simenon, a native of Belgium”.

And few have better expressed the spirit and soul of so many Irish towns and villages than Con Houlihan, one of the undeniably great figures in the Irish journalism of our age and among the very few whose work so transcends his chosen profession that it demands to be preserved. (Image from Rte.ie)